Chris Prior clarifies the mysteries of taxonomy and sheds some light on why we use certain Latin names and where

The answer to this question is, quite a lot if you know how to interpret it. The biologically trained will know all about these bits of Latin that crop up whenever organisms – in the current context usually trees or things that eat them – are mentioned in the text, but to those who are not so well versed in life’s intricacies, they must be rather mysterious. In this article, I will try to make things a bit more transparent.

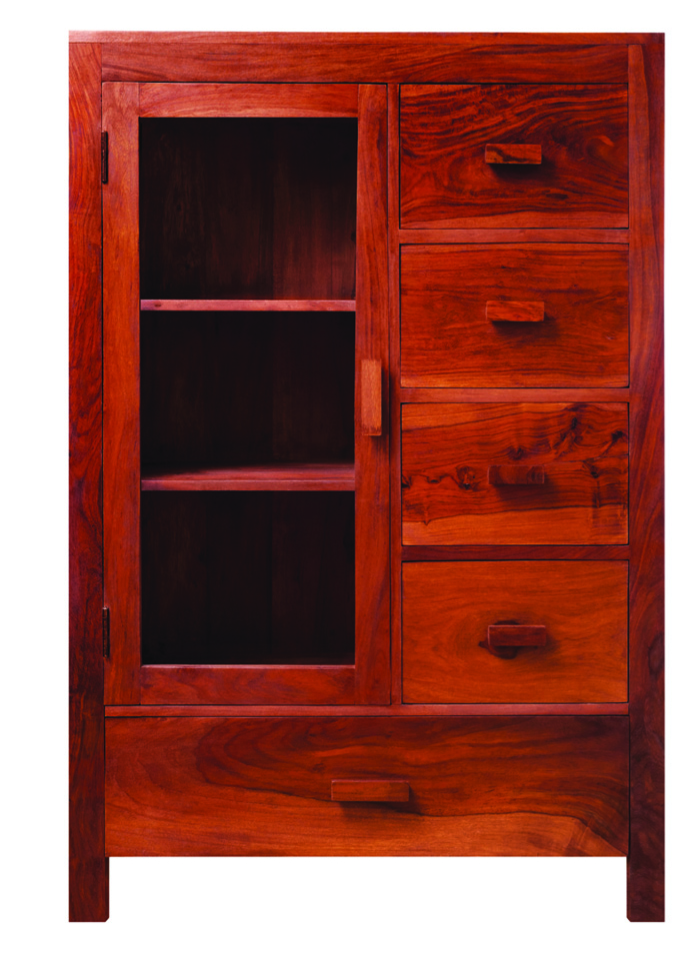

Walnut

The reason Latin names exist is to ensure we all know what we are talking about, assuming of course that we speak the language. Being a dead language is an advantage here, because it can’t change, or at least, only very slowly. Suppose an Englishman, an American and a Papua New Guinean are all looking at a cabinet in a furniture sale labelled ‘walnut’. To the first that will mean English walnut (Juglans regia), to the second its transatlantic relative American black walnut (Juglans nigra) and to the third New Guinea walnut (Dracontomelum mangiferum or D. dao) depending on which book you use – which isn’t related to the first two, but is called ‘walnut’ because the timber looks like the English one.

If this sale is in England the piece is likely to be made of J. regia, which will puzzle the American and the man from Papua New Guinea because it won’t look like what they know as ‘walnut’ – the Papua New Guinean version is similar, but not identical. If the Latin name had been on the label, at least everyone would have known what they were looking at.

How does it work?

Let’s start with the species, while noting that there are ranks below species, for example, variety. Each species is distinct in certain key features, usually those associated with the reproductive organs. This is not because taxonomists are obsessed with sex, but because those sexual parts, the flowers in the case of plants, are less variable than other parts. Those species with similar but distinct characters are grouped together in the same genus: Juglans, in the case of our first two walnuts. Similar genera are then gathered into families: our two Juglans are in the Juglandaceae, but Dracontomelum is in the Anacardiaceae. The story continues upwards until we reach the fundamental division of plants into Angiosperms – broadleaf trees – and Gymnosperms – conifers – which are, broadly speaking, hardwoods and softwoods respectively. The genus and species names when used together are called the Latin binomial.

The truth behind the system

Before Linnaeus – see sidebar – appeared on the scene, there had been attempts to classify organisms, for example on shape, size or colour, but these were imperfect because they failed to indicate underlying relationships. Lots of plants have red flowers or spiny stems, but those features don’t indicate the underlying genetic similarity. In Linnaeus’s system, we know that all the species in a genus will be closely related, so, for example, Juglans regia and J. nigra will have similar properties, whereas D. dao may look similar to both those, but those similarities will be coincidental: in fact, despite looking superficially similar, the Papua New Guinea walnut is significantly more dense than the other two.

Linnaeus and others who followed him were classically educated, since at that time there wasn’t really any other kind of education, so they all knew Latin and Greek. As a result, the names they gave to organisms used the languages they all knew and they communicated useful information, for example ‘nigra’ means black, and everyone would know that the wood was dark. That said, I can’t see that ‘regia’, which means ‘royal’, is better deserved by J. regia than J. nigra, except perhaps that it is so expensive that only royalty could afford it.

Demystifying taxonomy

The style of citation varies according to the audience to which the publication aims. F&C use an abbreviated form of Latin names, using the full binomial, for example, Juglans regia at first mention, the shortened version, J. regia thereafter. A more scientific and professional journal – which is not to say F&C isn’t thoroughly professional, only that it isn’t aimed primarily at scientists – would also cite the author at first mention and possibly also the date of their description – Juglans regia L. 1753. The name of Linnaeus crops up so frequently that he is often honoured by having it abbreviated to just L.

When taxonomists describe a new species part of the formality is that they must deposit specimens in approved institutions, such as museums. These specimens are described as types and if there is ever a dispute about the correct identification of a specimen, and such disputes are not uncommon because taxonomists have distinctly dogmatic tendencies, reference can be made to the type to aid the decision.

You could write books on taxonomy and lots of people have, but I hope this short piece has shed some light on that mysterious Latin.

The linnaean system

Carl Linnaeus 1707-1778 wrote much of his work in Latin, where he is known as Carolus Linnaeus; after his ennoblement he was known as Carl von Linné – in Latin, Carolus a Linné – but in modern literature he is usually referred to simply as Linnaeus. He was born in Sweden and spent some years in the Netherlands, where he published his Systema Naturae, which laid the foundations for the binomial system for naming and classifying plants and animals. He returned to Sweden and became professor of Botany at Uppsala University. Despite being in a relatively obscure corner of Europe, he became so famous that he received specimens from all over the world. For example, a large number of tropical seashells were named by Linnaeus.

The Linnaean system remains in use to this day for the formal naming and classifying of new species. Under this system, the species name given by Linnaeus always has priority, though the species may be moved to a different genus if subsequent study shows this to be more appropriate. The application of these formal procedures is complex and best left to the experts; I tried to do it once, and didn’t make a very good job of it.

Timeline of Carl Linnaeus’ life

- 1707 Carl Nilsson Linnaeus – or Carl von Linné – was born on 23 May, 1707.

- 1717 Linnaeus sent to Lower Grammar School at Växjö and soon discovered an interest in botany. He was also introduced to Johan Rothman, the state doctor of Småland and also a botanist. Rothman broadened Linnaeus’ interest in botany.

- 1727 At university in Lund, Rothman showed Linnaeus that botany was a serious subject. He taught Linnaeus to classify plants according to Tournefort’s system. Linnaeus, age 21, enrolled in Lund University in Skåne.

- 1728 Linnaeus decided to attend Uppsala University on the advice of Rothman.

- 1732 In April 1732, Linnaeus was awarded a grant from the Royal Society of Sciences in Uppsala for his expedition to Lapland. Linnaeus described about 100 previously unidentified plants. These became the basis of his book Flora Lapponica.

- 1746 Linnaeus was once again commissioned by the Government to carry out an expedition, this time to the Swedish province of Västergötland.

- 1751 Linnaeus published Philosophia Botanica.

- 1753 Linnaeus published Species Plantarum, the work which is now internationally accepted as the starting point of modern botanical nomenclature.

- 1761 The Swedish king Adolf Frederick granted Linnaeus nobility in 1757, but he was not ennobled until 1761.

- 1778 Linnaeus died on 10 January 1778 in Hammarby. His library and collections were left to his widow Sara and their children.