From unpromising student to award-winning teacher, Jamie Ward ran the gamut of woodwork teaching before moving into full-time making

Warwickshire-based Jamie Ward started out making furniture, then spent many years teaching before returning to the craft full time – but his school days, both as a pupil and as an educator, continue to make an impact.

‘Woodwork wasn’t my best subject at school – I wasn’t naturally talented,’ Jamie admits. His school woodworking teacher focused on the talented students, giving the rest less attention, and Jamie left school not quite sure what he wanted to do – although he had a bias towards making, as his father was an architect and his mother was interested in interior design. ‘My dad said, get yourself a trade, so I signed up for a joinery course at Mid-Warwickshire College, which is now Royal Leamington Spa College,’ he recalls. Jamie studied full-time – that meant five days a week, and he even had to do PE. ‘Nowadays full time would be about two days a week,’ he says.

‘I wasn’t bad at school, but I didn’t really engage. When I went on the course in Leamington I had to pull my socks up,’ Jamie says. ‘I started to get good grades, was always on time and made a good impression on my course tutor.’ Thanks to that good impression the tutor recommended Jamie for a job opportunity at a small, family-run joinery company in Coventry, where he started out making reception desks, windows, doors and stairs. Not long after, the company was taken over and became more production-oriented. Many of Jamie’s colleagues left, but he stayed on, mass-producing windows, doors and stairs on large machinery for companies such as Redrow, Barratt and David Wilson Homes. ‘I bought my first house at the age of 21 with a lad I was working with, and we spent time renovating this house,’ he says.

After a few years Jamie felt he wasn’t progressing in his career, or enjoying what he was doing. So he decided to sell up and go to university. He was advised to start his furniture journey with a two-year HND, then went on to take a three-year degree course at Buckinghamshire College in High Wycombe under professor Philip Hussey. ‘The course opened up my eyes to design and where I could go in the industry and utilise my skills. Up to that point I had been working for nine years, but now I was using the skills I had learned in joinery on windows and doors to go down the fine furniture route,’ Jamie says.

‘I worked hard and graduated with a first-class degree in 2001. Going back to my days at school, which I had left with no qualifications and with woodwork as one of my worst subjects, I found I had slightly put to bed the ghost of my school time where I didn’t work hard enough. I was a late developer – it took me until my late 20s to achieve what I should have done when I was at school.’

But first of all, I would ask, would I have it in my own home, and is the quality there? If I’m asking myself if this is acceptable then I know it isn’t

Learning curve

After graduating, Jamie started running the manufacturing arm for a small business that designed and made furniture for high- end clients, helping to set up a workshop and buy machines. ‘We worked for people like Paul Smith, the owner of the Swatch company and a Microsoft developer,’ he recalls. ‘Their kitchens were bigger than the floorspace of the whole house I grew up in. I was taught at university that I would be working for people in these households and environments, but having grown up in two or three-bed semi-detached houses, the wealth was eye-opening.’ While he was working in this role Jamie also started his first teaching job, leading an evening class at Royal Leamington Spa College. ‘I got that teaching job and I still teach the same class now, 23 years on,’ he says. ‘It is a Tuesday evening furniture workshop: students come in and I teach them basic woodworking skills. Some students stay with me for many years, some just come for a term.’

During the day he was working for a cabinetmaker named Roland Day, doing a wide range of jobs which showed Jamie both the variety of work that was out there, but also the crucial importance of attention to detail. ‘Roland taught me detailing perfecti on,’ he recalls. ‘I remember taking something to him and asking, is this all right? He said: If you are asking me, you know it is not. Go away and do it until you know it is right.’ He also spent some time working for a fine furniture company in Honeybourne outside Evesham. In 2008 Jamie returned to Royal Leamington Spa College full-time, starting out as a technician instructor and going on to become course leader and curriculum leader. This meant a return to education for him as well – he did three years of teacher training to graduate a third time. ‘There have been lots of gowns and mortar boards,’ he laughs.

Jamie set out on a grand tour of woodworking colleges around the country – which he notes are not in competition with each other because of their geographical spread. He set up a group of course managers who collaborated and shared ideas about managing the challenges of running further education courses in a way that worked for students but also made ends meet for struggling colleges. ‘It was very good to have that supportive network,’ he says. ‘Being a course leader is a challenging job. Teaching is very rewarding, but the students don’t see what you are doing behind the scenes: keeping things together, looking at qualifications and funding, and making sure the leadership teams are happy.’ He also became a liveryman for the Furniture Makers’ Company. As part of his work there he teamed up with local places of historic interest, for example making benches for a local castle, and arranged for lots of talented guest speakers to come and give his students a taste of the different things that could be out there for them in the future.

But over the years, as the college fought to keep its courses financially viable, Jamie was put under increasing pressure and his contact time with students made more and more difficult to achieve. He watched colleagues take redundancy, and in 2019 his own position was made redundant. ‘I was given a choice: I could stay and have my employment reduced from five days to two-and-a-half days a week. I didn’t take long to decide I wanted to move on and take redundancy.’ It may have been quick, but the decision wasn’t easy. ‘It was a hard thing to leave the workshop where I had trained myself as a 16-year-old,’ Jamie says. ‘I’m 55 now, so I was in that workshop for all the years in between, barring the 14 years I was at university and working. It is a great workshop and we have had great projects in there. It was set up in the 1960s and there are still receipts for the machines bought in 1963 and 1964, and the original teak parquet floor. I don’t want to see that workshop lost, and it was hard to walk away.’ But he still gets his teaching fix at evening workshops.

A departure

When Jamie first started working for himself in 1996 he was given a caricature of himself with his own furniture business. ‘It took me until 2019 to achieve that and get to the point where I was actually going to work for myself,’ he says. He had had experience of setting up a workshop for the first company he worked for after university – but not of doing it on his own budget. Over three years he built a timber shed in his garden from scratch, learning green woodworking, making large mortise and tenon joints and even cladding the roof. He finished the project in July 2019.

Jamie started work immediately to get money coming in, hanging gates and fixing squeaky floorboards on his local estate. Taking advice from award-winning furniture designer and maker Richard Williams, he started marketing himself locally with a view to progressing from there. ‘I didn’t have a workshop but a shed, so I couldn’t do a huge amount,’ he recalls. ‘I needed to get my reputation going. How do you get work when you haven’t got anywhere to do the work or anything to fall back on?’ What Jamie did have was plenty of contacts with experience in the world of furniture making, and one suggested he get himself an Instagram account, which he used to build his reputation more widely, drawing around 16,000 followers over six years. At the same time he publicised himself on his local Facebook page and got business cards printed to distribute around his home. By chance, the printer knew of a business looking to rent out a workshop bench, so Jamie found a place to work, in an old carpet factory in Warwick. ‘It was a massive space with a spray booth that really attracted me,’ he says.

He started getting commissions, but most of these were for doors and joinery, rather than the furniture he really wanted to make. He made a pair of bedside tables from solid ash, then got a customer who wanted an understairs storage unit. ‘I made one for them and it just took off,’ he says. Although these units are in demand, Jamie does have to explain to customers the difference between a carpenter who will build the whole thing working from a van in their driveway and probably charge less, and himself: a trained cabinetmaker making hand-cut dovetails, spraying everything and using higher-end materials. This led into more fitted furniture commissions and wardrobes, and most of Jamie’s work today is fitted pieces.

During lockdown Jamie discovered a Victorian farm near the village of Hatton outside Warwick which had a disused barn that had been used for storing farm equipment. Shortly afterwards he found himself looking for a new workplace, and ended up taking on this former milking parlour and renovating it to become his own workshop. He concreted the floor to make it stable enough for his machinery, made doors and benches and created a spray room. He also made his own Anarchist Tool Chest, based on the book of that name by Christopher Schwarz, from spare components. Jamie collects Stanley planes and has some favourite tools, including his Skelton dovetail saw. ‘I have even got a hacksaw I made at school in CDT lessons when I was 14: we bent metal into the shape of a hacksaw and powder-coated it,’ he says. A speed-sander is the next thing on the wish list.

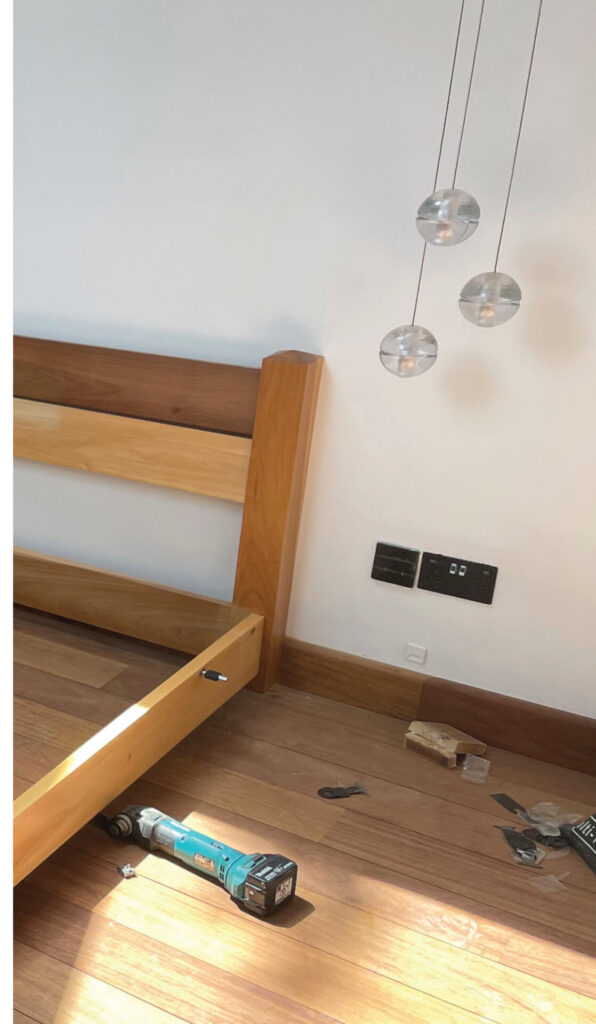

‘We are geared towards fitted furniture, but we can make stand-alone furniture,’ Jamie says. Recent jobs have included a wine chiller cabinet made from solid iroko and three beds made from tulip poplar, and he loves both building the furniture and seeing the homes of his wealthy clients, many of whom work for local business Jaguar Landrover.

Although he sometimes wishes he were making stand-alone fine furniture, he feels his late start in the business has left him without the time to build the necessary reputation. ‘If you want to be the next John Makepeace or Gareth Neal, you have got to be really determined and have time on your side. Yes, I would like to be making fine, stand-alone furniture: for one thing, it is much easier to make it. You drive to a customer’s house, walk in, have a cup of tea, walk out. With a fitted piece you could be in there three or four days – it is a much longer process in a customer’s house and there is much more than can go wrong. So time was, yes, I would have liked to be making fine furniture, but I don’t feel I have the time to build up my business now I’m in my 50s.’ In fact the good thing about fitted furniture is it takes him right back to his production-oriented start, making windows and doors. ‘I’ve come back to that, but now I’m in control of it,’ he says.

Finding a Niche

Inspiration comes from all over: automotive design, other makers, classic designers such as Charles Rennie Mackintosh, arts and crafts, natural proportions such as the Fibonacci sequence, and his favourite designer Paul Smith. ‘But first of all, I would ask, would I have it in my own home, and is the quality there? If I’m asking myself if this is acceptable then I know it isn’t,’ he says. One of the key things Jamie is working on is his own unique selling point. ‘What is a Jamie Ward?’ he asks. ‘I used to spend a lot of money on Paul Smith, on classic English-cut suits or jackets. They were understated, but when you opened up the jacket, inside there would be a very bold check. That was his USP. What does it mean to be a Jamie Ward, so that when someone walks into a room they know it is my work? In fitted furniture I don’t know – I’m still working on it.’

His advice to other makers is simply to do what you say you are going to do. ‘Be on time, and if you can’t or don’t want to do something, politely decline. The same goes for customers: if you have asked someone to come out and quote, go back to them and communicate yes you want to go ahead or sorry it’s too much and let them down gently. Don’t just ignore them. I always try to make sure I don’t go to see someone and waste their time if the budget isn’t there. College didn’t teach me that – it is about understanding how you work with potential customers and how you need to attribute your time.’ ‘My advantage is that I have mixed with lots of people who are successful, and who have given me all these little pointers. It is very hard for young makers coming out of college.’ He notes that colleges are struggling to get students for furniture and woodworking courses, and that this is having a knock-on effect on the industry. ‘How do we get young people to come into our industry when my own children sit in their bedrooms on computers and iPads not making things?’ he asks.

‘We used to go into the woods and make a den, but they don’t do that so much as we did in the 1970s and 1980s. Attracting young people to vocational schools is much harder now than it was then, and the furniture industry has been affected. Furniture courses are closing down because people don’t want to go on them. So how do we train the next people and draw them into these skills?’

When he’s not working, Jamie loves running and has run five London marathons to raise cash for Children With Cancer UK, but having his own business has meant he has been running a bit less this year. His two children are now young adults and he is teaching his daughter to drive, and he likes to get out for walks and weekend city breaks around the UK. ‘In the Midlands there are a lot of places within easy reach. As long as I get my fix of culture, design and a cathedral or some interesting architecture, plus something to eat, I’m happy,’ he says.

jamieward.com | @jamiewardfurniture