Andy Coates says it is time to bring the versatile scraper back in from the cold

Scrapers are something of a controversial subject. Some turners regard them as little more than a poor relation to gouges and are critical of those who use them. Quite why this should be eludes me. The scraper is one of the oldest tools in the woodturner’s armoury, but that does not mean it no longer has a place – far from it. Wherever there is a gougemark or a shape to refine, the scraper is there to assist.

They are usually made from a single bar of steel, either flat or round, and have a bevel ground on them. This is not a bevel to rub as is the case with gouges, but simply a means of providing an edge and reducing the resistance to a cut made with the burr on that edge. They are a simple tool but can take some practice to master.

There are arguably three basic groups of scrapers: forming tools, which are not at all common today; finishing, or refining tools and hollowers. A forming tool is used to create repeatable shapes, such as is achieved with a bead-forming tool, for instance. A finishing or refining scraper would be something like a multi-tipped sheer scraper; a hollower might be something as unassuming as a simple domed scraper, or more exotic such as

a deep hollowing tool. Within each group there are many variants and there are also those scrapers that cannot be pigeon-holed in one group alone. The truth is the variety is almost infinite because scrapers can be custom-made to serve a single purpose. The primary function of a scraper, however, is to refine a gouge-cut surface in readiness for abrading. Let’s start by looking at the scrapers.

Basic scrapers

These are mostly used for refining surfaces ready for abrasion. Some variants are also detailed here.

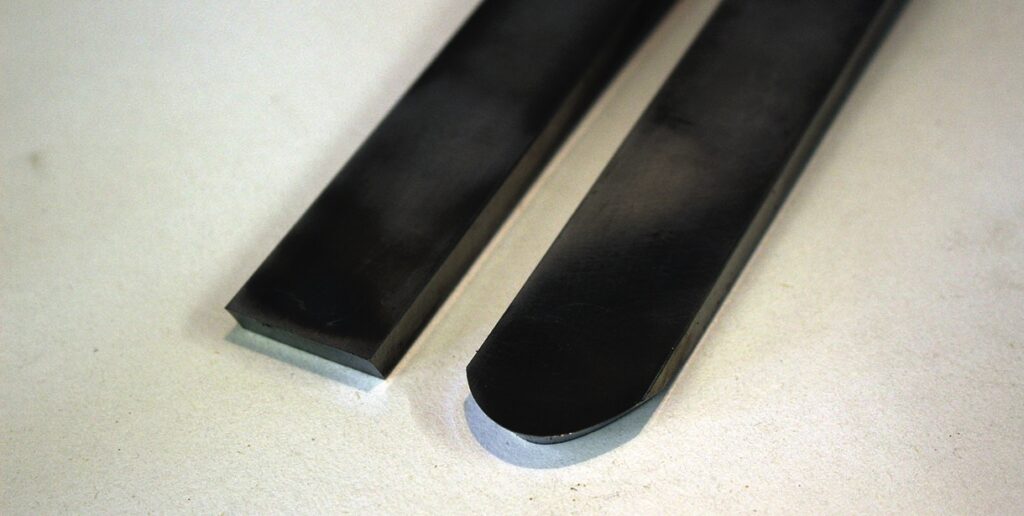

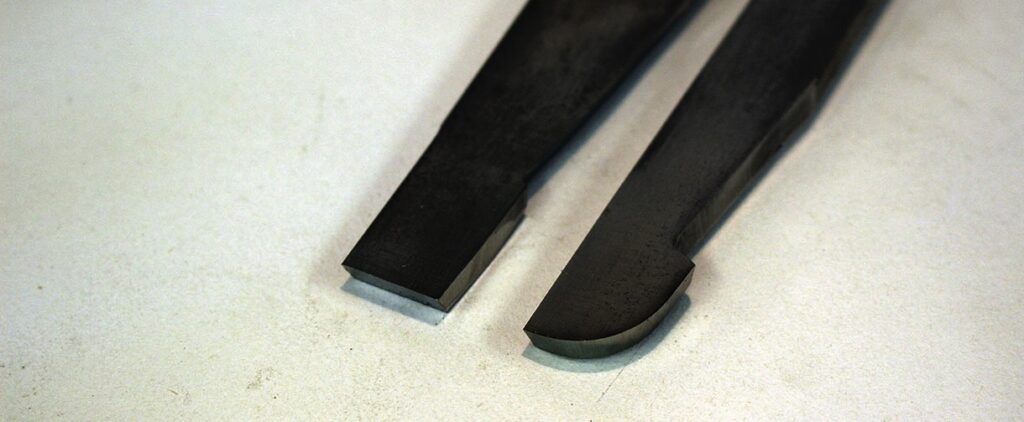

The standard straight and round-ended scrapers can be used for refining and hollowing small end grain objects. Bevel angle, as for all scrapers, can be anywhere between 40° and 80°, and they are used without the bevel rubbing, and flat on the toolrest at a trailing angle (cutting edge lower than handle).

French curve style scrapers: these scrapers can be used flat on the rest or canted to about 45° to give a shear scrape. They can be used on interior and exterior curves. A negative rake version can be ground to provide a more user-friendly scraping experience.

Box scrapers, straight and round: both also cut on the side, and can be used flat on the tool rest, or angled at 40° to 45°. They can be used for stock removal on end grain and for refining the inside walls of boxes and small vessels. Modified scrapers: a negative rake curved scraper and a negative rake rounded-end scraper. Both have a combined angle of about 60° between the two bevels. The negative rake scrapers are ideal for hard, dense, exotics, bone, and acrylics. On common woods the main advantage is a significantly reduced likelihood of a catch.

The modified straight scraper has a skewed end and side cutting negative rake box tool. The tool is used flat on the toolrest in a slightly trailing mode.

The left-hand tip leads the left-hand edge down the wall of the box and the tool handle is pushed away from the body to bring the skewed end flat in the base of the box.

Multi-taskers

This set comprises a wide range of variants, with roles other than simply refining pre-cut surfaces, although some can still function in this role.

Multi-tip shear scrapers of various sizes: these scrapers usually come with three shapes of head – square, teardrop and round. The teardrop tip often has a straight face for use on outside curves. These tools are a useful and cost-effective option.

Multi-tip gooseneck scrapers for hollowing the neck area of small end grain vessels through a small entry hole: these are usually used for light hollowing or shear scraping the interior of hollow vessels initially hollowed with cutting type tools. A range of styles and sizes of various hollowing scrapers. Some employ a fixed, replaceable tip, others are simply bent bars of tool steel. They may appear primitive compared to some modern tooling, but each has its place and use, and is often invaluable at the right time.

Forming tools: these range from an almost antique pair of forming tools to bead-forming scrapers and captive ring tools. This kind of tool is primarily used on spindle work, and can leave a poor surface which may require considerable abrasion to finish. Their advantage is the ability to create repeatable shapes of a given size and form with ease. This is a ’shop-made copy of an original David Ellsworth hollowing tool. Arguably the forerunner of all hollowing tools, and included here as evidence that simplicity is not always a bad thing. As a tool it works incredibly well, and all other scraping type hollowing tools derive from it.

Grinding

Scrapers come from the manufacturers pre-ground and will be usable as supplied. In order to regrind the tool when it gets dull it is best to use a table support at the wheel of your bench grinder. Some turners maintain that the more coarse the wheel, the bigger the burr produced. However, if the top surface is polished and a finer grade wheel used, the burr produced will be more consistent, providing a finer finished surface. The compromise here is a less robust burr which will require regrinding more frequently.

The burr formed on the grinding wheel is produced on the opposing surface to the face you grind, so on a conventional scraper the burr is formed on the top edge of the single bevel. On a negative rake scraper the lower bevel is re-ground and the burr forms at the front edge of the top bevel. Negative rake scrapers can be honed on the lower bevel only to refresh the burr between re-grinds.

Some turners prefer to regrind scrapers upside down to produce a burr that is raised over the edge. The only issue with this method is the low placement of the tool at the grinder wheel. If a secure table is used this should not present an issue.

Tool presentation

1) Flat on the toolrest in a trailing mode – handle higher than cutting edge, and light pressure (almost just the weight of the tool) applied against the wood surface.

2) Scraper angled at between 30°-45°, scraping in shear mode.

As with all tools there are subtle refinements in usage that you will discover – and possibly adopt – but for all the flat-to-toolrest presentations you must ensure that the tool is used absolutely flat on the toolrest, otherwise a catch can occur with potentially devastating results for your workpiece. The reduced resistance to the cut experienced in shear scraping mode removes this likelihood.

Scrapers in action

Now let us look at the range of uses and presentation methods.

The curved scraper can be used flat on the toolrest and on faceplate work the cut travels downhill, from the foot of the bowl towards the rim. In order to scrape in the opposite direction you will need to have a scraper ground on the opposite side.

The curved scraper can be used at 45° to the wood. The tool in this mode cuts much finer, with far less resistance to the tool edge, making it a cleaner, finer cut with far less chance for a catch.

The multi-head scraper can be used horizontal or at a shear angle on internal or external curved surfaces. The various cutter forms allow you options as to what tip to use.

The negative rake curved scraper is ideal for use on the interior of a bowl. The tool is presented flat on thetoolrest in a trailing mode to produce a very fine cut which is easy to control.

The domed negative rake scraper can be used on internal curved surfaces or to produce a flat surface. On a flat surface like platters and trays the tool is used in trailing mode on the centre axis and traverses the surface from centre to rim. A straight across scraper can also be used but the corners are prone to digging in if presented poorly.

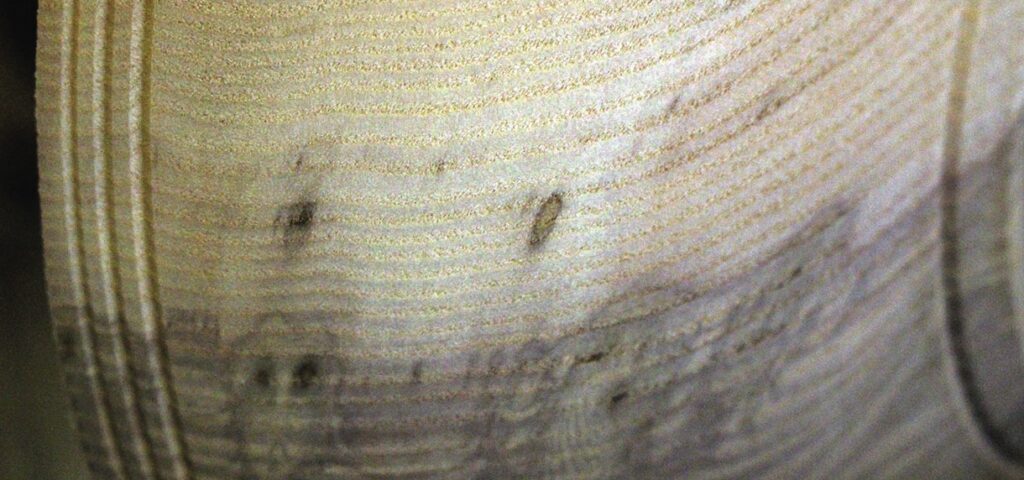

Round-nosed scrapers can be used to hollow a small work like goblets. Scrapers work very well on close-grained woods such as yew (Taxus spp.) and sycamore (Acer pseudoplatanus), and a blemish-free finish is possible. The only limitation is depth: 75mm is probably the maximum reach for a tool with a standard length handle.

Goose/swan-necked scrapers are used to hollow out hollow forms and similar vessels. The cutter is presented to the wood at a slight trailing angle. The tool must always be supported on the straight section of the shaft only. The tool can be used for stock removal and finishing cuts.

Shaped box scrapers are ideal to hollow a shallow box. The tool is presented flat and trailing. The shaped head allows the tool to be used on boxes and forms with a shallow undercut at the rim.

The modified box scraper, skewed front and side negative rake, can be used to refine internal box shapes. The handle is pushed away from the body to bring the skewed edge straight on tothe base of the box for flatting and finishing. With the handle pulled back the side edge will cut the side wall.

A bead forming scraper is typically used in trailing mode for the initial cut. As the cut progresses the handle is gently raised until the cutting edge breaches the formed bead. The finish is likely to require abrasion but the shapes are repeatable allowing for a run.

Sharpening scrapers

Let us now give some thought to the general procedures for sharpening and honing scrapers.

Grinding is achieved by using a supporting table at the wheel. The table should be as close as possible to support the tool fully. Ensure the table is securely locked down. Grind with a light touch. The conventional method is illustrated in the pictures below.

Here the tool is laid down on the top face of the scraper and ground upside down. Some turners prefer this method as it drags the burr up over the cutting edge producing an upstanding burr.

Scrapers can be refreshed by honing with a diamond hone between re-grinds. Hone in the direction you want the burr to be raised. A polished top surface will result in a more consistent burr along the edge, but this is not strictly necessary. When re-grinding negative rake tools only the bottom bevel is ground. This may be in the conventional or the upside down orientation and honing can be carried out to reduce the number of visits to the bench grinder.

And this is what scraping is all about: producing a clean, level surface free from gouge marks in readiness for abrading. It is not uncommon to be able start two or three grades of abrasive finer than usual after a successful scraped finish.

NB: Multi-tip and some dedicated hollowing scrapers will require the tip to be removed from the tool shaft and

fitted to a tip holder for re-grinding.

Remarks

Critics claim that scrapers are prone to catching, which is perhaps unfair. A fairer assessment might be that users are prone to presenting the tool in a manner in which it can only catch. If you experience difficulties with a flat scraping tool inside bowls, consider a round-bar, or half-round, multi-tip tool. The round underside allows the tool to be used inside bowls and vessels at a variable degree shear angle, which reduces resistance to the cut and consequently the tendency to catch. If you struggle on the outside of vessels, or on spindle work, consider a negative rake version of the scraper.

Try to keep in mind that a scraper doesn’t work in the same way as a gouge. It won’t take a better cut if you push it in to the wood. What will happen is that the burr will disappear into the wood almost immediately and the edge will dig into the wood, causing a catch. Try to develop a weight-of-the-tool policy, where the pressure applied is almost nothing other than that exerted by the mass of the tool.

Scrapers have been around a long time. Historically turners would use them on ebony (Diospyros spp.) and other hard exotic woods, bone and ivory because gouges cut these materials quite poorly. For a time they seem to have been virtually abandoned but more recently have re-surfaced, largely thanks to a resurgence of use in the US by turners such as Stuart Batty and Cindy Drozda, but for a long time we had our own master in Bill Jones, so it is due for a revival. There’s much to be said for using a scraper appropriately. Why not give it a try?