Guest editor Les Symonds takes on an unusual heritage project

One of the many advantages of living in the Snowdonia National Park (or Parc Cenedlaethol Eryri, as it is truly known) is the amazing mix of industrial heritage set in a spectacular landscape and I am indeed blessed to have examples of each of those features right on my doorstep. I can look out of the window of my workshop and see the hills of the southern fringes of the park, while also hearing the unmistakable ‘toot’ of the whistle of a steam locomotive. Bliss!

Last year, one aspect of that very steam railway came a little closer to my workshop door than I had expected when the chimney of Alice, one of its steam locos, was delivered for me to make a wooden copy of the crown at the top of the chimney, which a foundry could then use as a pattern for casting a new one. It seemed that the existing crown was made of spun sheet steel and incorporated a lot of welding, which failed to meet the standards of integrity for the true act of restoration of such an historic item.

The plan of action

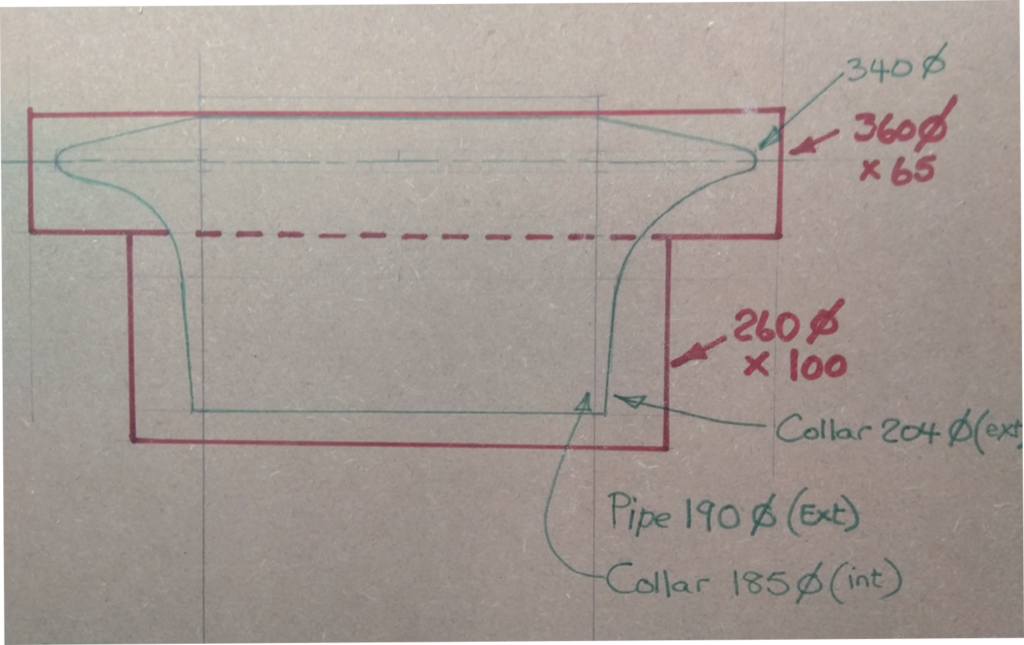

As is always the case with such projects, the first job was to make a full-sized drawing on a substantial background – not just a sketch on a sheet of paper. With this complete, I was able to overlay the dimensions of the chunks of suitable timber that I had in stock, until. I found a combination of two pieces that would be big enough to fit the drawing. The maximum diameter was 360mm with an overall depth of 165mm (14 3⁄8 x 6 9⁄16in), and these were the finished dimensions of the cold iron.

That’s quite an important point to note because the dark art of pattern making needs to incorporate an element of exaggerated measurements to allow for the contraction of the molten metal as it cools and shrinks in the process. Traditionally, pattern makers would have had a set of grading rules; effectively wooden rules, similar to the steel rules that we all use on a daily basis, but these would have slightly oversized measurements. Understandably, different metals have different rates of shrinkage, so a different grading rule would be found in the pattern maker’s workshop, for each metal that he would be making patterns for.

In my case, the foundry supplied me with a ‘coefficient of expansion’, effectively a percentage by which cast iron shrinks as it cools, so all my measurements were made oversized by that percentage and two big lumps of sycamore were prepared for the lathe, a socket joint cut between them and they were then glued together with a generous amount of PVA adhesive.

Cutting the profile

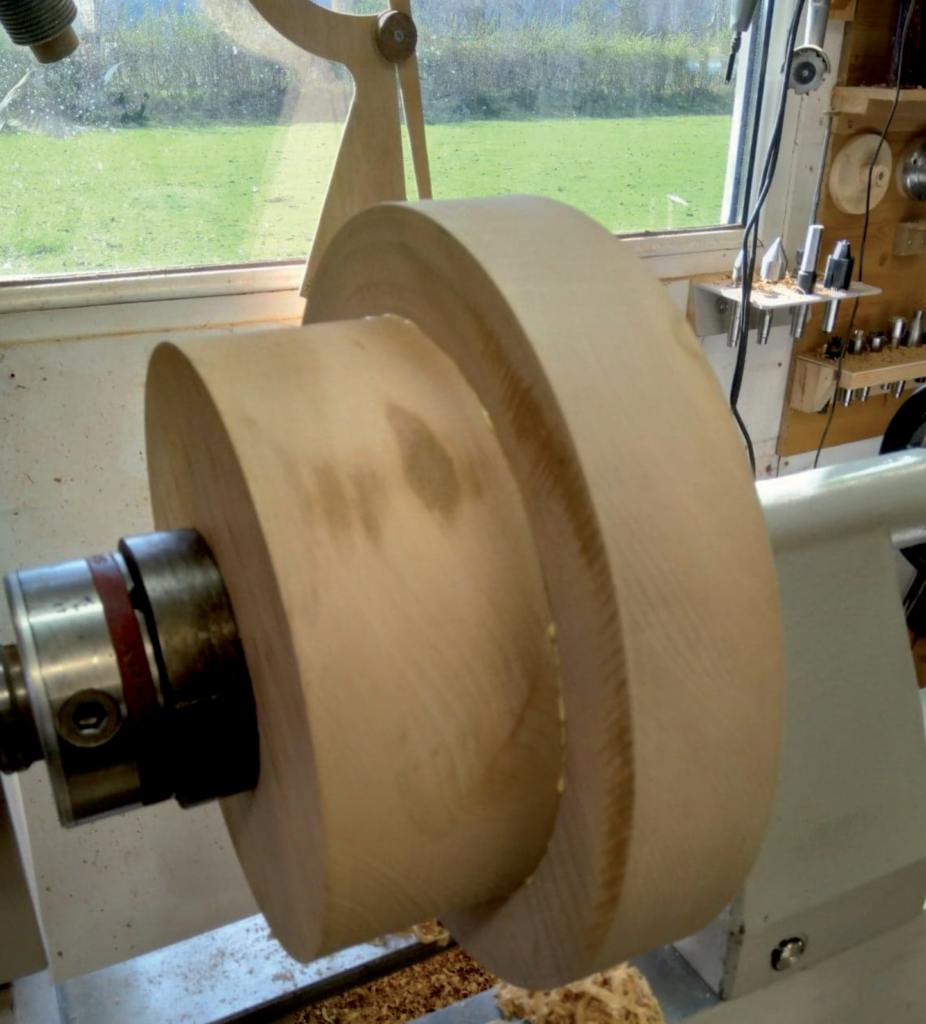

Work progressed in the usual manner, getting the workpiece on to my largest set of chuck jaws as early on in the process as possible. Pieces of timber as large as this can incur a fair degree of movement during turning, especially in this case because the whole of the centre and much of the outside were being turned away, so work needed to progress quickly.

A sheet of tracing paper was laid over the full-size drawing and the profile traced on to it, then it was transferred on to a piece of thin ply. This was cut out and tried for its true shape against the face of the existing chimney, before being used as a template to perfect the curve on the wooden pattern, then the gentle downward slope on the top of the crown was cut and sanded before I turned my attention to hollowing the core.

The external diameter of the chimney pipe of the loco was a peculiar size, at 190mm (75⁄8in), so the internal bore of my pattern needed to use that measurement as a starting point, but also had to incorporate an allowance for the shrinkage of the molten iron and for the railway’s engineering workshop to skim the inside of the bore down to an exact match to the chimney pipe.

This all resulted in an internal measurement of 180mm (7¼in), which was later to pose a problem. In the image showing the bulk of the hollowing completed, you will see that deep down in the core are the chuck jaws, which are about 110mm (43⁄8in) diameter, with a good ring of timber still around them. The problem therefore lay in finding a means of reverse turning the crown so that the remainder of the core could be cut out and the underside skimmed to the crown’s overall height. Standard reversing jaws would not be strong enough to hold such a large, deep workpiece, so a more radical solution needed to be found.

Reverse turning the crown

Sometimes, the simplest solutions can be the best, and this was to be one of those times. Off the shelf in my timber store, I took a bowl blank that was a little larger in diameter than the core of the crown, set it on a faceplate and turned it down to a snug fit inside the core, leaving a distinct shoulder of a larger diameter at the headstock end. Once I was happy that this was a good fit, I drenched it with lashings of water and pressed the crown into place. Within seconds the blank had swollen and taken a vice-like grip on the crown, the shoulder on the blank ensuring that the crown sat perfectly squarely upon it. This was not the right time to take a coffee break.

The remainder of the core was cut away before the timber began to dry out and shrink again. I had a few issues with a slight wobble, probably somewhat less than a millimetre, but there was sufficient tolerance in the dimensions I was working to, to accommodate this, especially as the bore of the finished iron casting was to be machined to fit the chimney.

The first firing

I took a back seat while the guys at the foundry worked their wonders with a sandbox and molten iron, then a phone call came in to say that the casting had been delivered to the engineering works, so I was welcome to call to see it – and there it was, alongside my wooden pattern. I doubt very much that you could tell from the photograph, but close inspection showed that the iron version was, just as we had planned, several millimetres smaller than the wooden pattern. The lads at the railway’s engineering works, in mounting the iron crown on to a lathe, had to be as inventive as I had been when reverse turning my core. Let’s be honest, though, my job of skimming out the wooden core was as nothing compared to skimming a cast-iron version.

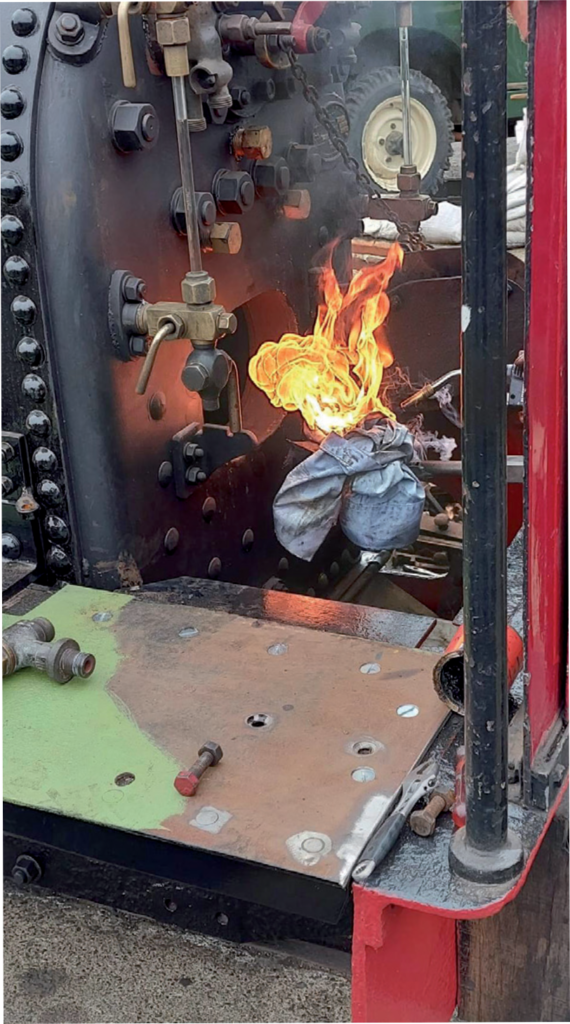

It was a good few months later that Alice was finally ready to fire up and put into steam, so we drove down to the sheds and stood back as the traditional oily rag was lit, upon the fireman’s shovel, and nudged into the firebox. It took a few minutes, but then the first signs of smoke appeared to much applause.

Our local heritage railway, where Alice hauls her trains loaded with tourists, runs alongside the largest natural lake in Wales and it’s where I sail on days off (and sometimes on days when I should be working), and it brings me an enormous amount of pleasure to catch fleeting glimpses of the top of her chimney as she rolls on by.