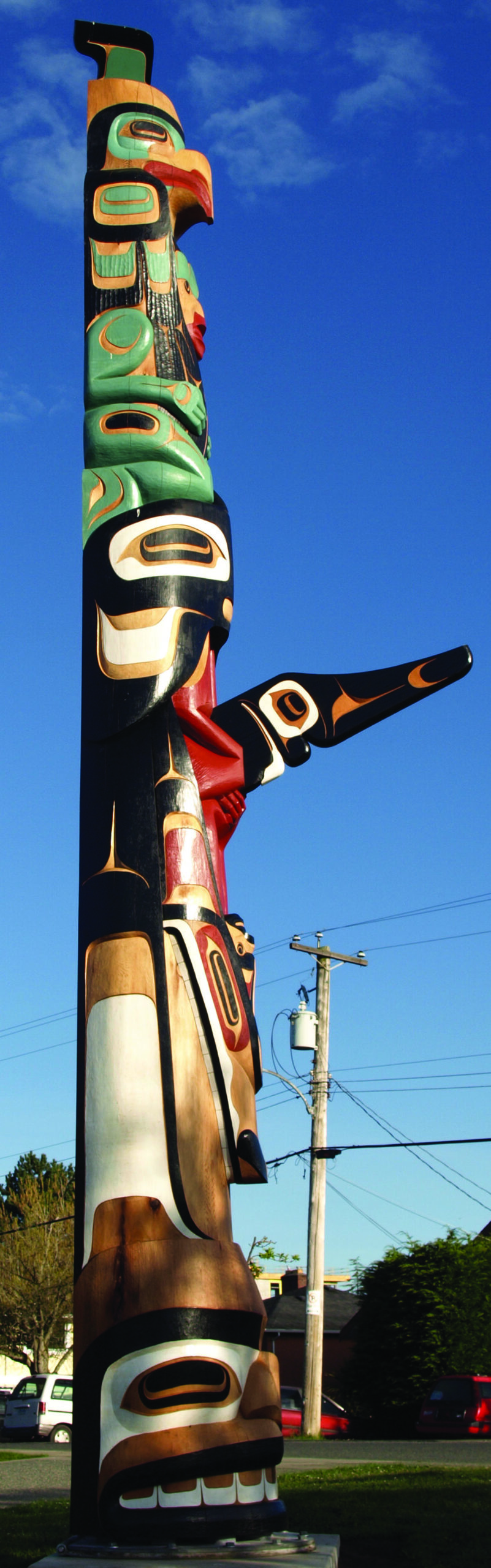

The Qweesh-hicheelth (Midst of Transformation) Totem Pole

Dave Western gets a rare chance to see the making and raising of a Totem Pole

Dave Western gets a rare chance to see the making and raising of a Totem Pole

It’s not every day a totem pole is raised in a suburban neighbourhood, but the area of Victoria Tillicum, located in Victoria, BC, Canada is home to a trio of these artistic masterpieces. Carved to honour and represent the three First Nations of Vancouver Island, the poles have all been commissioned by the Victoria Native Friendship Centre and carved in Salish, Kwakwaka’wakw and Nuu-chah-nulth styles. Residing on the ancestral land of the Coast Salish people, the Friendship Centre provides services for First Nations people from both the Greater Victoria area and for those who have moved here from regions further afield.

Over the course of several years, the three poles have been carved by teams of youth apprentices working under the guidance of master carvers. The poles have been sponsored by the Friendship Centre through an exciting initiative called the Eagle Project, which enables First Nations youth to learn valuable life skills, such as first aid and tax planning, as well as experience hands-on training with a master First Nations craftsman.

The youth were involved in every phase of the creation of a 25 foot monumental totem pole and worked beside the master as the pole progressed from its arrival as a raw log to its final raising as a monumental artistic statement. Along the journey, they were trained in the use of traditional hand-tools, learned about First Nations art and legend and gained insight into their cultural history and its importance. The totem pole has become such an iconic symbol of North American First Nations culture that it may come as a surprise to learn they were only carved along a thin strip of land bordering the Pacific Ocean reaching from the present day Puget Sound region up to the Alaska Panhandle. Hollywood stereotyping and ubiquitous gift shops selling ‘Native crafts’ from coast to coast help reinforce an erroneous image of the totem pole being common to First Nations across North America.

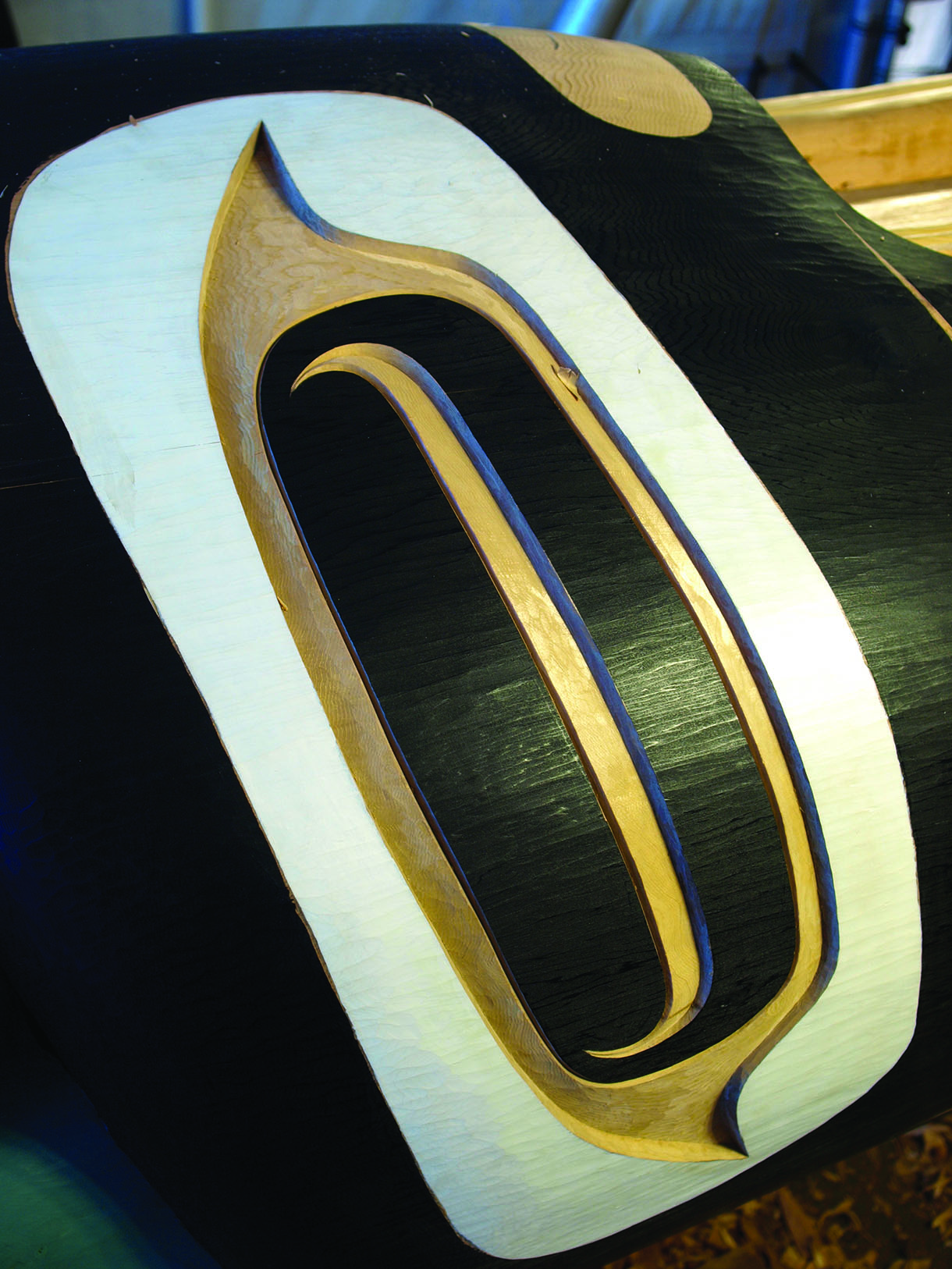

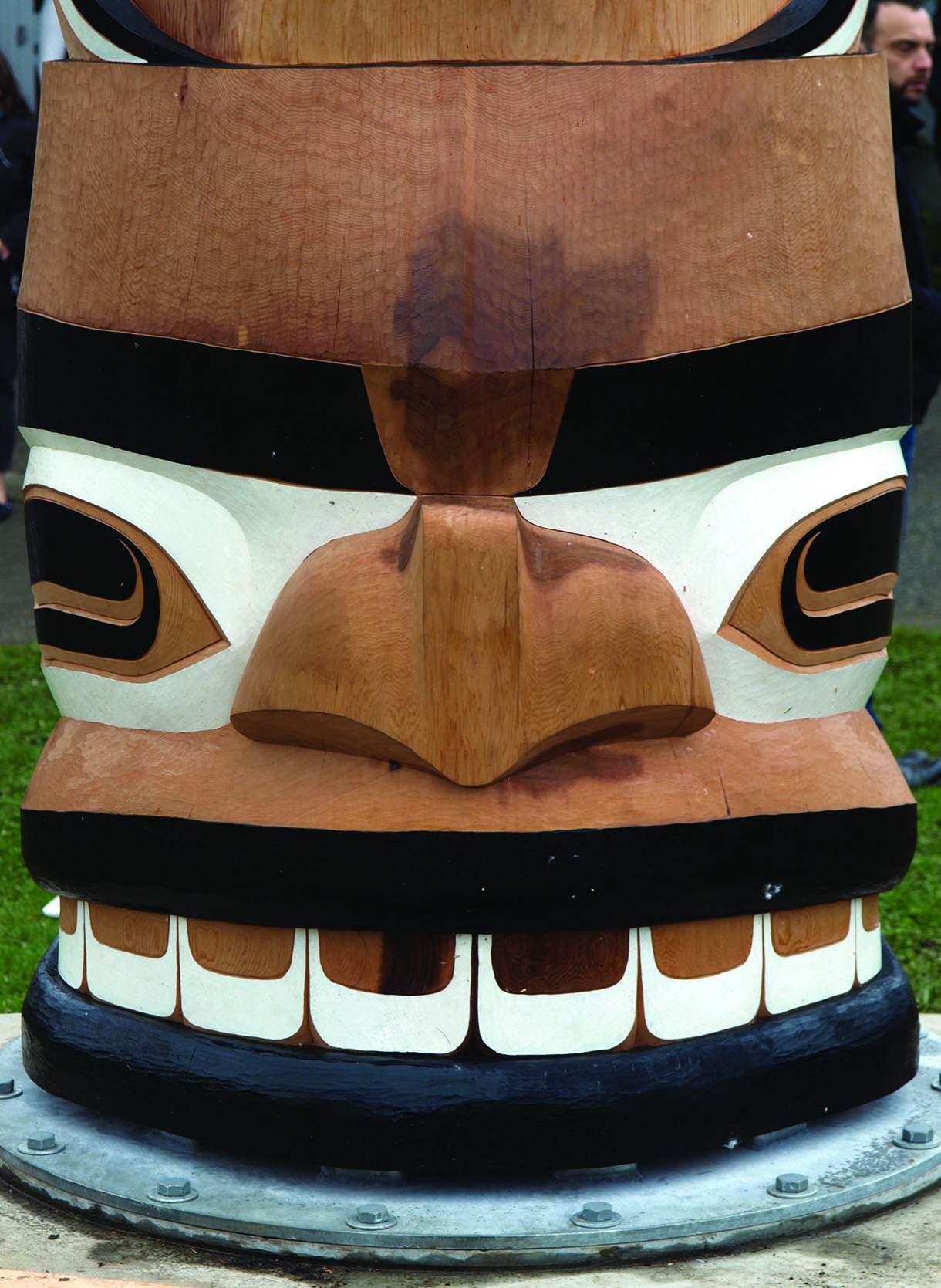

A Nuu-chah-nulth style human face emerges from the roughed-out pole

Despite its massive size, every detail of the pole is crisply carved

Even the name is confusing as there is nothing ‘totemic’ about them. First Nations people did not worship the poles, rather, the poles served to document family histories and the family’s right to own certain crests and legends. Totem poles were also raised to honour important or deceased members of the nation. Many supported the main beams of a house building while lending prestige and beauty to the structure. Occasionally they could be erected to shame neighbours who had left debts unpaid. Today, they might be raised to commemorate important events or to cement relationships. After hundreds of years of colonial domination, they remain a powerful statement of First Nations pride and independence. Poles are most commonly carved from the mighty western red cedar (Thuja plicata) a native tree of the Pacific Northwest coastal area which also supplied generations of First Nations people with material for clothing, shelter, transportation and art.

This most useful of trees is also rot and pest resistant, a valuable attribute in the notoriously damp environment of the coastal region. Totem poles as we know them are a fairly recent addition to NW Coastal art and have largely been developed over the last 200 years. Although poles existed prior to the arrival of steel tools, they were likely a great deal less ornate and most certainly few in numbers. Even with modern tools carving a pole is an enormous task; in the days of stone tools it would have been an immense undertaking.

The Tools

With the increased availability of metal tools during the early part of the 19th century, it became easier and quicker to carve a monumental work such as a totem pole. The designs became more sophisticated and the carving ever deeper and more elaborate, First Nations carvers became masters in the use of several types of axes, adzes and ingenious bent knives. Today, electric and gas powered chainsaws help carvers remove excess material rapidly and accurately, but the fine work remains the domain of hand power.

Adzes

NW Coast carvers use two main categories of adze. The elbow type adze features a blade fastened to a resilient wooden handle – typically fashioned from a section of alder (Alnus rubra) branch and crotch –

which is swung much in the same manner as a European sculptor’s adze. Typically, a carver will have several types of elbow adzes. For rapid rough hogging of excess material, he may employ a robust lip adze, whose aggressive curved blade is perfect for wasting large pieces at a time.

Elbow adzes (L–R): finishing adze, straight medium adze and lip adze

Apprentice Travis Peal uses an elbow adze to rapidly clear excess material

The medium sized gutter adze

has a lower curved blade, suited for detailing work such as shaping roughed out forms, hollowing or cross-grain cutting. A straight-bladed version of this same size adze is often used in mask carving and for clean levelling of wood surfaces. Small finishing adzes featuring straight or slightly curved blades are used for the fine texturing and detailing common to good quality poles and woodwork.

The D adze is named for its distinctive shape and can be used for roughing out work or fine detailing. It is a favoured tool of First Nations carvers; prized for both the speed with which it removes material and for its ease of control.

The pole’s designer and master carver, Moy Sutherland Jr., uses the D adze to swiftly shape and texture an area

Bent knives

The bent knife is the perfect tool for cutting and defining the deep, sweeping curves which characterise NW Coast First Nations carving. The unique blade can cut on the push or pull stroke, with or across the grain, following concave or convex curves. Because the blades are rarely true radiuses, one bent knife can replace a dozen or more European-style carver’s gouges.

A selection of hand-made bent knives with a variety of blade shapes

Hand maul

This remarkable stone maul was used to pound wedges and to tap European-style chisels. Not a common tool since the arrival of metal tools, it was used on this pole but requires a good deal of strength and skill

to operate effectively.

Stone hand maul

Carving the pole

Carving a totem pole is a major challenge. Even finding a suitable cedar log of sufficient length, width, straightness and clearness can be difficult. Once selected, it must be felled and shipped to the work site, where it is trimmed to length and prepared for carving.

A centreline was struck the length of the pole and callipers used to maintain the symmetry of the design. Large areas of material could now be removed with chainsaws and adzes.

Artist Moy Sutherland Jr. uses a chainsaw to cut the log to carving length

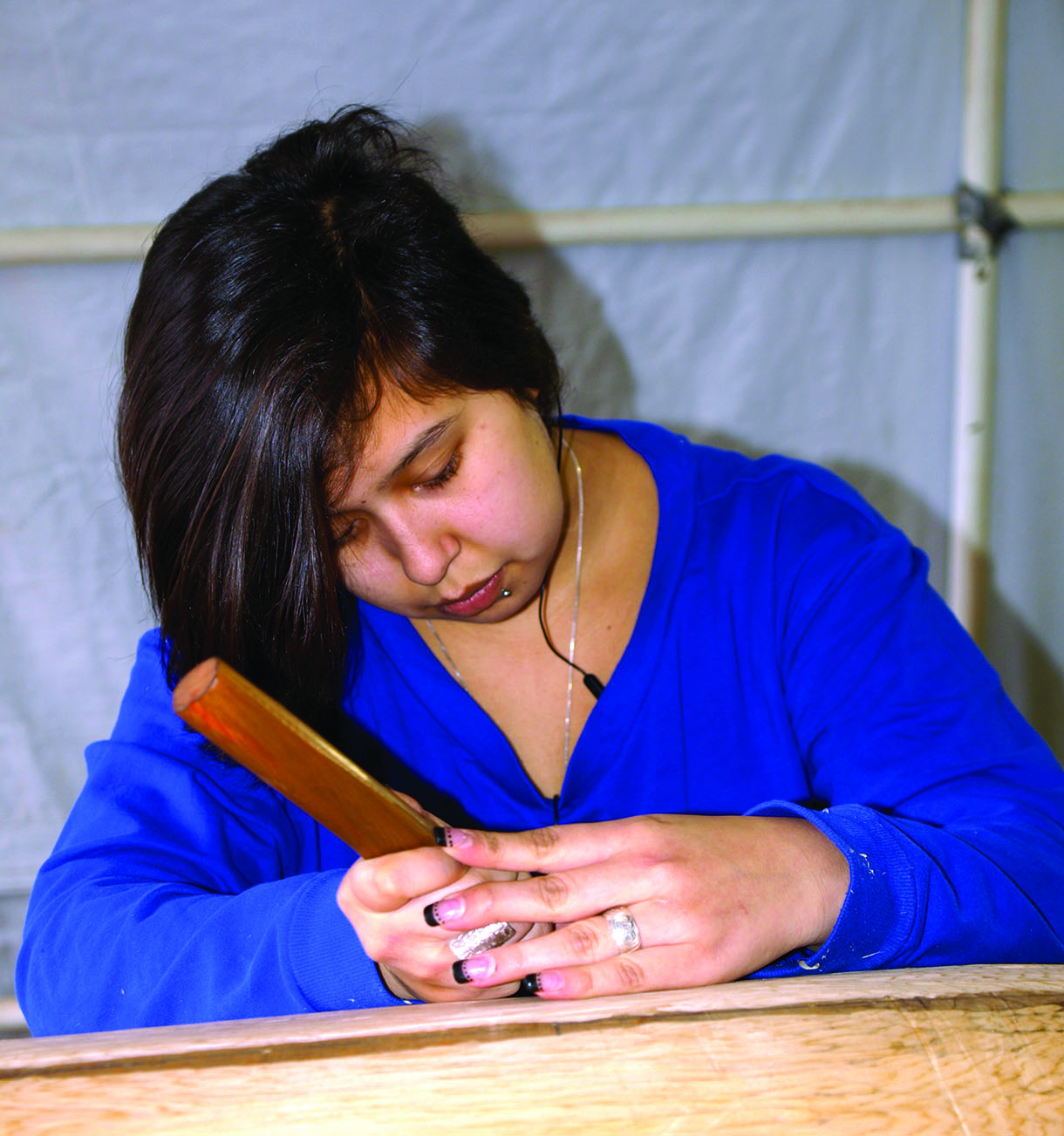

With the roughing out largely completed, the details could start to be refined and irregular surfaces cleaned up. At this point, the apprentices started to become familiar with their tools and the behaviour of the wood they were cutting. Many hours of smoothing and shaping took place. Bent knives and finishing adzes were used to level and texture the surfaces. Apprentice Joslyn Williams concentrated on fine finishing with the bent knife.

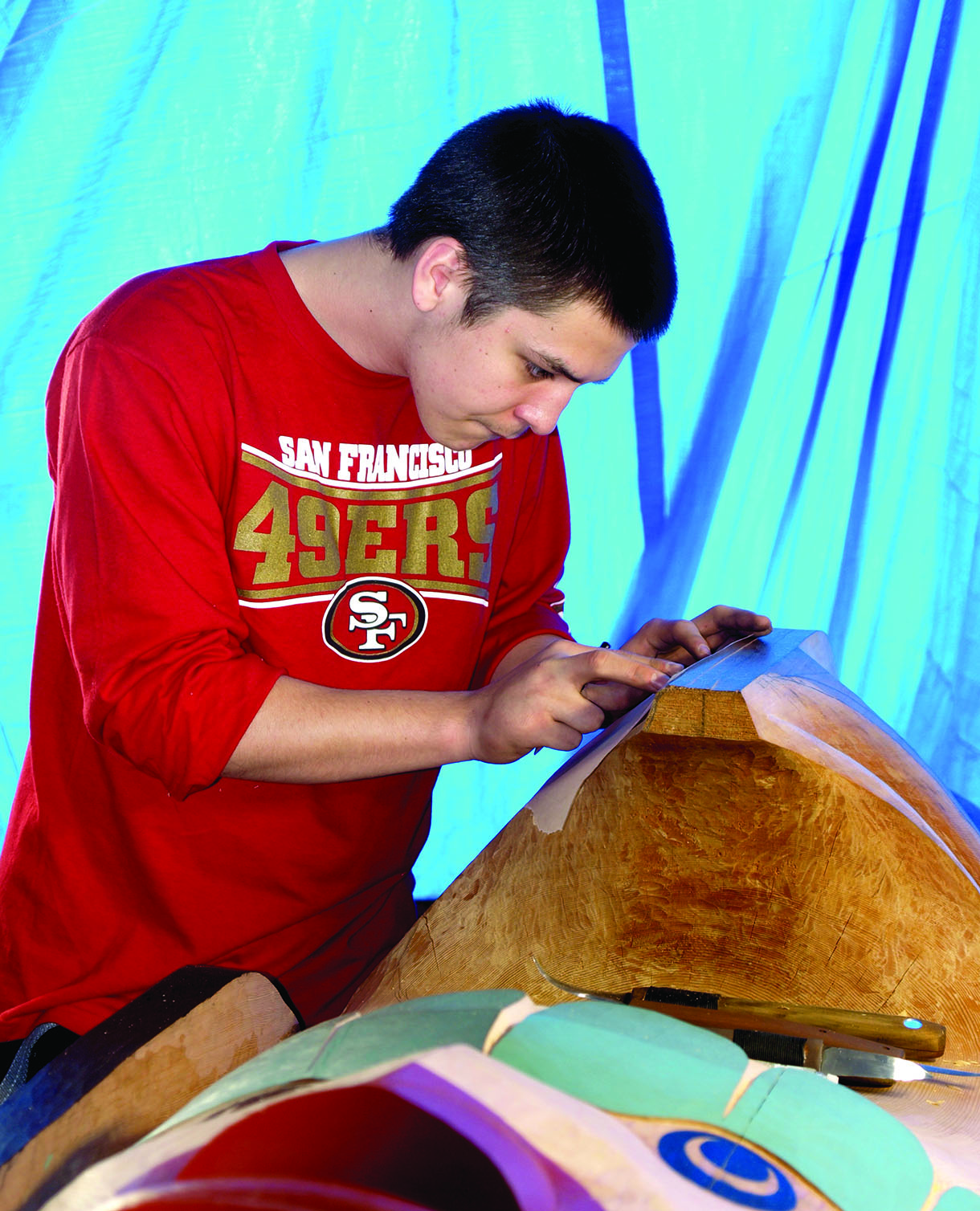

Different sections of the pole will have differing textures and finishes. An adzed surface contrasted with the smooth area which apprentice Jordan Gallic cleared with a large bent knife. The tools had to be kept razor sharp so the soft cedar grain could be cut cleanly and not simply torn or frayed. Jordan put a lot of effort into attaining that perfect edge.

As material was cut away and the final shapes emerged, the detail lines were drawn and redrawn. Apprentice Dawson Matilpi-Peel used a tracing paper template to ensure that details taken from one side of the pole matched up with the other side. The centreline remained critical for keeping the pole in line and symmetrical, and it was one of the last things to be cut away. It was a full team effort to get the details tidied up and to ensure the various components of the design were visible and in order. Moy Sutherland made certain that all the cuts were deep and sharp, refining sections that were still beyond the apprentices’ ability.

Detailing work can begin

Joslyn Williams uses a bent knife to smooth

Jordan Gallic sharpens his bent knife

Dawson Matilpi-Peel transferring the design

A centreline is crucial for maintaining symmetry

Even while perfecting continued, certain areas of the pole were ready for painting. Apprentice Tyssis Fontaine was the painter of the group and was tasked with the job. Paint was applied before the final detail carving was undertaken so that when final cuts were made, the division between painted and raw wood was particularly crisp and clean. The master refined all the edges and performed the final deep cutting that brought each painted area to life.

With all the painting and deep detailing completed, the apprentices gave the pole a coat of oil to lend it some protection from the weather. Traditionally, poles were expected to eventually succumb to the elements and rot away. This was considered a normal part of the process.

In the quiet before all the excitement of the move and the raising, the pole waited in a now quiet carving shed. The dorsal fin and the Thunderbird’s ears would be added just before the raising to minimise chances of damage.

Tyssis Fontaine begins painting the pole

The painting accents important features

The painting complete

Protective coating is added

The pole is ready for moving

Viewing the Pole

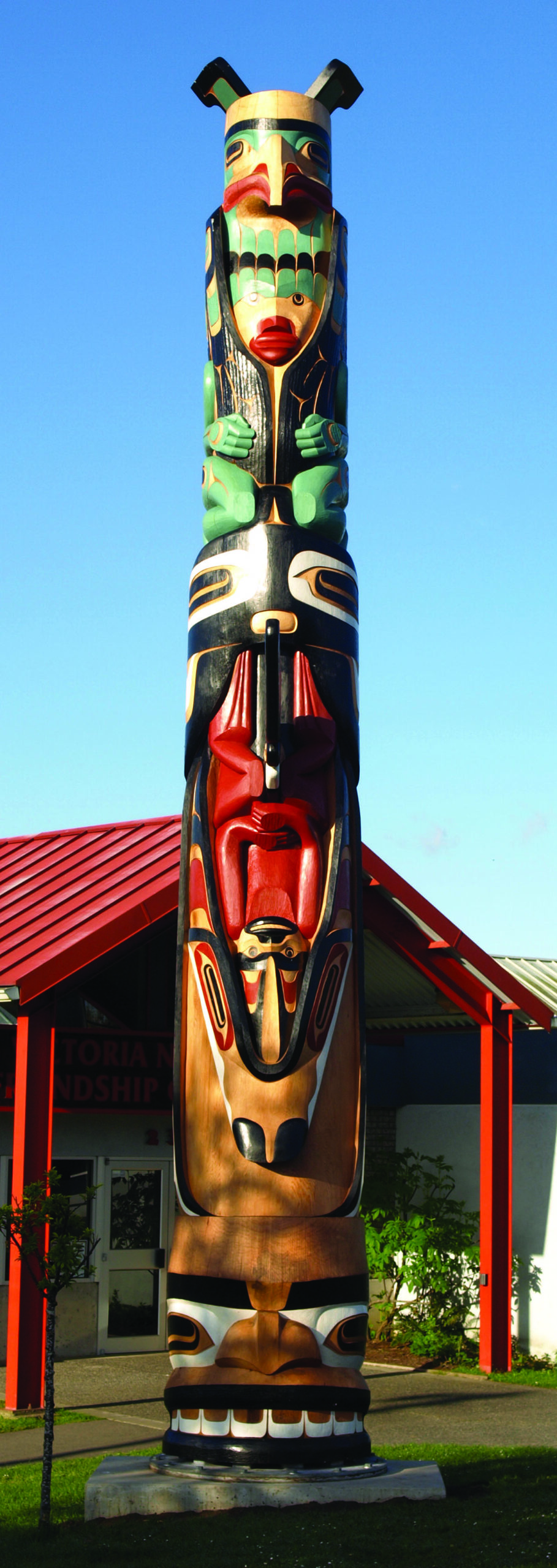

The Qweesh-hicheelth pole, (from the Nuu-chah-nulth word meaning ‘in the midst of transformation’) was designed and carved in the Nuu-chah-nulth style by master Nuu-chah-nulth artist Moy Sutherland Jr.

The pole is comprised of two main figures, the Thunderbird and the Killer Whale along with a number of smaller figures, each in a state of transformation.

The Killerwhale’s face is presented in mask form at the base of the pole

Revered by the Nuu-chah-nulth as the ultimate whaler, the Thunderbird could swoop down from its nest of mountain ranges and snatch a whale from the sea

Raising the pole

Lifting a 261/2 foot long, 6000+ pounds carving from a prone to an upright position was a process fraught with difficulties and many dangers. Nowadays, lifting cranes and hinge plates take a bit of the worry out of the job, but it is still not a process for the faint of heart. Despite its mass, the pole was surprisingly susceptible to bumps and dents and great care was taken to protect it through the entire process. The pole was taken from the carving shed to the raising pad the evening before the lifting ceremony, to give time for final touch-ups and ceremonial blessings.

Once the pole had been jack lowered from its carving cradle to ground level, it was then slid on heavy-duty aluminium rollers from the covered shed to a place where it could be accessed by the lifting crane. Foam padding was positioned around the pole to protect the carving before large lifting straps were secured in place. The crane then took up the weight of the pole and the pole could be manoeuvred above the truck.

Transportation

The pole was then gently lowered onto the truck deck for transport to the raising site. A level bed of dunnage was built on the truck deck to secure the pole and to ensure the strapping was not trapped when the crane boom was lowered. The carving could be easily dented or damaged, so this was a moment of high anxiety for all concerned.

Driving a massive crane and pole through narrow suburban roadways required a bit of traffic control and

a very skilled operator. With the truck in place, the pole was cautiously lifted back off the deck and moved to the raising pad. At the bottom of the pole, the thick steel hinge plate would be mated to its other half, which had been bolted to a level concrete pad. Although the crane carries the weight of the pole, care was taken not to bump it as it was being swung around.

With the pole lowered in place, the two hinge halves were joined with a tightening pin in preparation for the next day’s lift. In the old days, a hole would be dug and the bottom several feet of the pole would be left uncarved so that as the mass strength of the village was put to use in the lifting, the pole would drop into the hole and would be a bit more controllable. Gruesome legend suggests that slaves would occasionally be thrown into the pit to cushion the blow of the pole’s landing, but this rumour has never been archaeologically verified.

Steve Lawrence moves the pole into place

The raising

Raising day was a time of great excitement for the carvers and for the community. Many hundreds of guests attended and were greeted by the Coast Salish people on whose land the pole will stand. There were blessings, speeches and dances, with many wearing traditional regalia. It was an exciting and festive occasion! In the brief moment before all the action started, the master and his Eagle Project team took the opportunity to be proudly photographed beside their achievement.

A pole raising is a time of great pride and importance for First Nations people

Tradition

In First Nations culture, the artist has a responsibility to ensure the traditions and skills of many centuries are passed down to the next generation. Artist Moy Sutherland takes his responsibility seriously and is proud of the effort his youth put into their project. With the ropes securely fastened to the pole and the lifting cradle in place, the raising ceremony could begin. Under the watchful eyes of the elders, over 100 First Nations youth prepared to start pulling the rope, which would raise the pole to its upright position. With instructions from the master, a song of blessing from his family and encouragement from spectators, the rope pullers began the slow process of hauling the pole upright. Care had to be taken to keep the lifting motion sedate and controlled at all times.

With the pole well underway, the lifting cradle began a controlled fall toward the ground, supported by a couple of strong carvers. At this point all the pole’s weight is directly on the lifting line. Just prior to the pole becoming upright, a bumper was placed inside the hinge to stop the pole from gaining too much forward force from the landing. If the bumper wasn’t there, the pole could shoot ahead, rip up the hinge and crash onto its face.

Lift coordinator Steve Lawrence and metal smith Jake James replaced the bumper with successively smaller bumpers until the pole had arrived at the upright position and could be bolted into place. This was a tricky and delicate operation as the pole’s entire weight had to be lifted up a tiny bit so the blocks could be slid in and out; not a job for amateurs. With the pole in place and firmly bolted down, all that remained was for the strapping protecting the pole during the lift to be removed.

This job was trickier than it appears as heavy metal pulleys and connectors had to be removed and lowered without bumping the delicate woodwork.

The pole begins 200 years of watching over the neighbourhood

The celebration

As the pole began its life and many years of watching over its surroundings, guests were invited to attend a traditional lunch of muwac (deer stew) and bannock bread hosted the Friendship Centre. During the celebrations, the carvers were honoured for their work, with the apprentices being given gifts, ceremonial blankets and honorary Nuu-chah-nulth names.